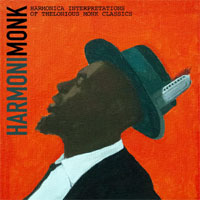

Randy Weinstein • HarmoniMonk: Harmonica Interpretations of Thelonious Monk Classics Random Chance Records RCD-50

At the keys, Monk’s modernist hesitations, clusters and gap-toothed chord voicings could suggest an itinerant boogie pianist who’d entertain logging-camps laborers by coaxing sound from broken-down untuned uprights missing 20 keys and a pedal. That earthy, physical, resistant sound is kin to the black rural shout of Sonny Terry’s blues harmonica, with its echoes of field hollers, its bent notes and hand-muted wah-wahs. Or to Grand Ole Opry harpist DeFord Bailey’s mesmerizing train-songs, anticipating by a half-century the non-stop circular energy of Evan Parker’s solo soprano sax recitals. With Sonny Terry in my ears before I got into jazz, the sound of jazz harmonica, epitomized by Belgium’s Toots Thielemans, struck me as simpering and nasal -- his tone is more classical than, say, that of mid–20th-century pop virtuoso Larry Adler, who knew the power of a judicious wah-wah. Now comes Randy Weinstein, making his first album as leader at 65, a New Yorker originally from Kansas City (where he recorded a few guest shots with singer Karrin Allyson), who’d spent seven years soaking up blues harp stylings in Chicago. HarmoniMonk documents his COVID-era deep dive into Monk compositions, and save for the ballad "Ruby, My Dear," we are far closer to Terry and Chicago’s whooping Little Walter than Toots. Weinstein has a blueser’s full-throated wail, displayed on the opening "Bright Mississippi" -- Monk’s line on "Sweet Georgia Brown" chords, with a bit of Bailey’s chugging momentum. Here and throughout Weinstein solos on chromatic harmonica, where a side-lever lets players reach the sharps and flats diatonic blues harps skip over; he touches on Monkish ‘wrong’ notes but never leans on them like they’re jokes. Harmonica wants to sing out, and Weinstein lets it. Overdubs abound; "Bright Mississippi" is just for him and guitarist Michaela Gomez, whose scratchy rhythm part is selflessly right, and whose out-front solo is bar-band raucous. Her syncopated staccato rhythm part, mixed low, propels "In Walked Bud," where she also slips in a mid-register walking bass line. Another highlight is "Green Chimneys," for chromatic harp and George Rush’s overdubbed arco and pizzicato basses, solo and in support. Rush returns on tuba, lagging behind the beat, for "Straight, No Chaser." There Weinstein layers lead and background harps, which converge to spotlight a few pithy Monk phrases. The arrangements aren’t overly fussy but do keep things varied. On "Bye-Ya" Weinstein cruises over a track from Clyde Stubblefield’s collection of grooves for sampling, his canned beat bringing out the harpist’s jauntiest phrasing. "Off Minor" gets Jamaican dub-style treatment: plenty of echo and stuttery riddim, with help from drummer Richard Huntley. Behind his chromatic lead, Weinstein deploys harp with MIDI-controller, to simulate lumbering electric bass and provide twiddly background atmosphere. It’s all audacious, but good taste saves the day. He comes to praise Monk, not bury him. The cheeky credits make clear this is very much a

home-recording project, studios including Randy’s bathroom and Gomez’s living

room. Weinstein credits himself with engineering, mixing, mastering and "general

audio signal fuckery." Chicago harp thrives on deliberate distortion after all. The

occasional ashcan sound quality fits a project that succeeds by never getting too slick,

or slapstick. |

ascinating to

hear how musicians have approached Thelonious Monk’s thorny compositions over time.

Early on, some folks played his tunes as if they were like anyone else’s, polishing

away the sharp corners. By the 1980s, young lions, among others, might imitate Monk and

his quartet, trying to seize their spirit. More recently, the best interpreters bring some

of their own quirkiness to the quirky material. So Fred Hersch’s 1997 "Five

Views of Misterioso" connects Monk’s skeletal blues to Morton Feldman’s

rarefied composing. NRBQ pianist Terry Adams (on his 2012 disc Talk Thelonious)

turns "Hornin’ In" and "Humph" into shitkicker rockabilly, and he

calls for back-to-back harmonica and pedal steel guitar solos on "Monk’s

Mood." That’s stretching the idiom in a good way.

ascinating to

hear how musicians have approached Thelonious Monk’s thorny compositions over time.

Early on, some folks played his tunes as if they were like anyone else’s, polishing

away the sharp corners. By the 1980s, young lions, among others, might imitate Monk and

his quartet, trying to seize their spirit. More recently, the best interpreters bring some

of their own quirkiness to the quirky material. So Fred Hersch’s 1997 "Five

Views of Misterioso" connects Monk’s skeletal blues to Morton Feldman’s

rarefied composing. NRBQ pianist Terry Adams (on his 2012 disc Talk Thelonious)

turns "Hornin’ In" and "Humph" into shitkicker rockabilly, and he

calls for back-to-back harmonica and pedal steel guitar solos on "Monk’s

Mood." That’s stretching the idiom in a good way.