A Pair of Audible Illusions and Some Reliable Capacitors

ack in 2018, Wilson Audio made an announcement that was easy to overlook, because it didn't introduce a new speaker or other audio component. Instead of a press release, CEO Daryl Wilson distributed a short letter stating that the company had "entered into an asset purchase agreement to acquire the manufacturing equipment and significant assets of Reliable Capacitors." What is Reliable Capacitors? A California company founded in 1978 that, as its name implies, manufactures capacitors -- but not just any capacitors. "RelCap," as it is informally known, caters specifically to the audiophile market, producing film capacitors of various types, as opposed to electrolytic capacitors. Among the differences between the two are the values -- film capacitors are generally much lower in capacitance than electrolytics -- and their longevity. Electrolytics go bad after years of use, while film capacitors remain stable, often indefinitely. The audio industry relies on both, but for different applications: film capacitors for line-level and phono circuits and speaker crossovers, and electrolytics for filtration and power supplies. Film caps of the type Reliable was famous for were used in many renowned audiophile products. The company's best-known product, the MultiCap (renamed AudioCapX), a multisection film capacitor that audio designer Richard Marsh invented, has been widely used in the audio industry for decades.

Why was Wilson Audio so interested acquiring in Reliable Capacitors that it was willing to purchase the company, lock, stock and barrel? First, its owner, Bas Lim, was 81 years old and wanted to sell. Second, Wilson had been using Reliable Capacitors in its crossovers for decades, and presumably the loss of that source of vital parts -- to Wilson Audio, crossovers are a big deal -- concerned the company enough that purchasing its supplier, instead having to build a relationship with a new owner, was paramount. So, as the TV commercial from decades ago went, Daryl Wilson liked the product so much that he bought the company. He sent a team of employees to California to learn each step of the intricate process of manufacturing capacitors before moving the company and its assets to Provo, Utah. It now operates from within the Wilson Audio factory.

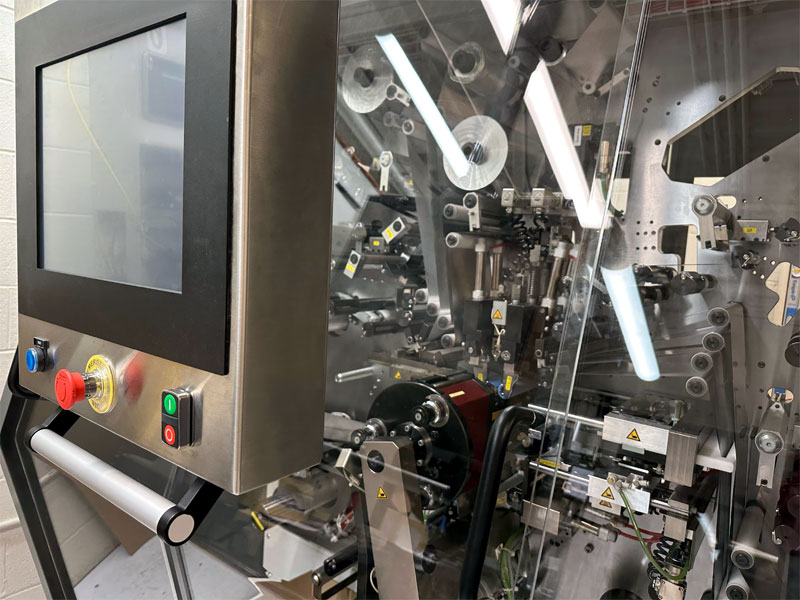

Film capacitors are products of science, but their manufacture for the audiophile market involves some real art too. The art comes in the creating and in the choosing of the dielectric -- the film material -- used. You don't just buy a machine to make film capacitors off Amazon. It is a specialized and very expensive piece of equipment that looks a little like an old-fashioned newspaper press, with all of its reels and tension rollers. The film material, which is wound sort of like tin foil on a cardboard roll, affects the sound of the capacitor. Tin is one of the best-known capacitor foils, but there are others that are more exotic, like copper and silver, and less exotic, like aluminum. The winding needs to happen at a precise tension, layer upon layer creating a finished capacitor of a particular capacitance and voltage. Some film capacitors are large, even huge, if the capacitance needed is very high, and others are small -- only slightly larger than a grain of rice. The same machine makes both to the tight specifications that customers, equipment manufacturers and consumers, require. Making capacitors is not for the faint of heart or the shallow of pockets.

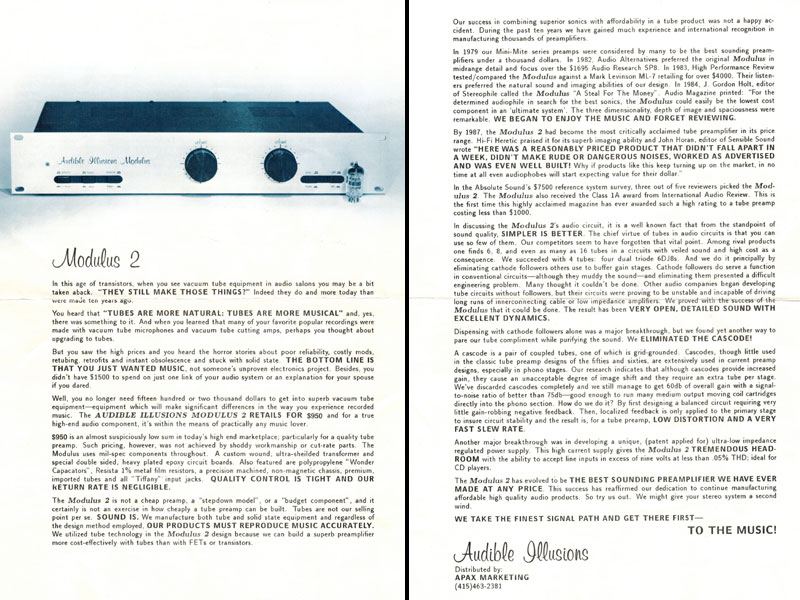

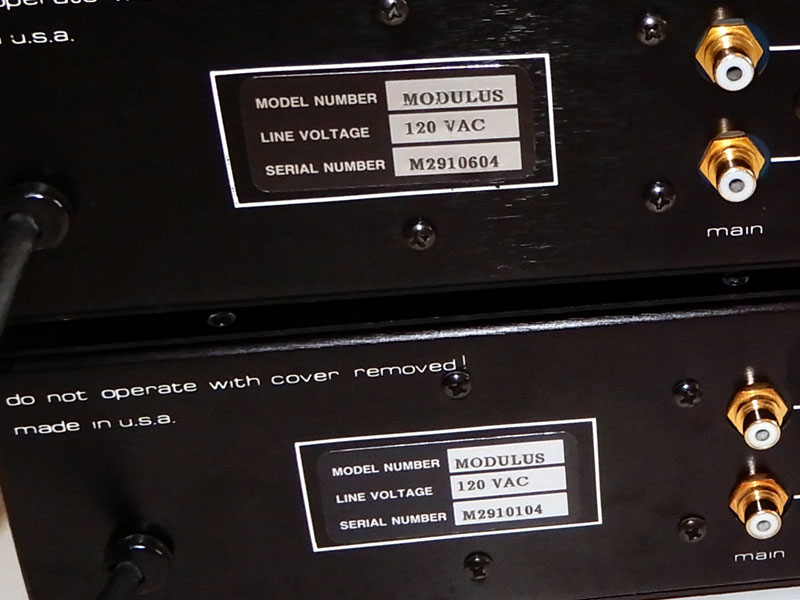

ow, the meat of this article. Back in 2016, I bought a used Audible Illusions Modulus 2D preamp from a local fellow who was liquidating the audio system of his wife's previous husband. I got it at a good price, $325, although it was untested, so there was a chance that it wouldn't work at all. I was willing to take the chance because the unit was in good, clean condition, and it came with the original manual along with some extra paperwork, including a sales flyer, receipts for tubes the owner purchased, and -- best of all -- a key for determining the age of the preamp from its serial number, which was M2910604. The "M2" apparently stands for Modulus 2; "91" stands for the year of manufacture, 1991; and "0604" means this was the 604th Modulus 2D manufactured. Audible Illusions made a lot of Modulus 2 preamps -- there were A, B, C, and D versions. Its list price started at $595 in 1985 and increased to $795 by 1991. The Modulus 2D was the last in the line; a 2E was listed in The Absolute Sound Guide to High End Audio Components for 1991/1992, but it probably became the Modulus 3, which was launched the following year.

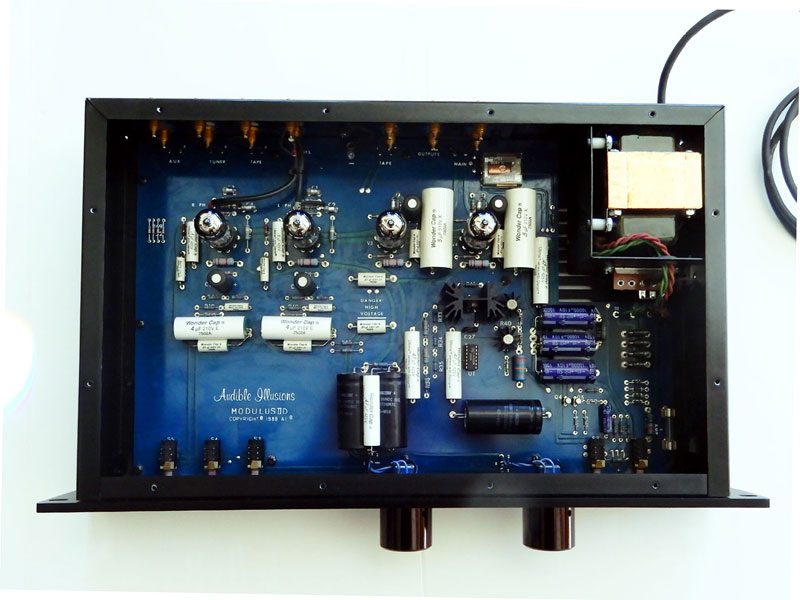

All versions of the Modulus 2 use two matched pairs of 6DJ8, 6922 or 7308 tubes, one pair in the line stage and one in the phono stage, whose gain is suitable for moving-magnet or high-output moving-coil cartridges. It's a rather bare-bones preamp, in the spirit of less circuitry making for better sound. In stock form, the Modulus 2D is not a warm-and-fuzzy-sounding tube preamp. It was meant to be a competitor with the various Audio Research preamps of the day, albeit costing less, so the sound is clear and open, detailed without harshness, with very good bass definition. Its onboard phono stage is also very good, extending the line stage's sound to analog playback. The Modulus 2 has two sets of main outputs, uses binary pushbuttons for input switching and a pair of volume pots (no balance control) that do not include detents; you have to study the position of both whenever you make any volume changes (more on this below). It inverts phase from its main outputs, so you need to account for that somewhere else, mostly likely by flipping the speaker connections. I used this unit as purchased (with new tubes) in my office system, but after I crossed paths with a very skilled local technician, I decided to have some parts -- electrolytic capacitors and some hot-running rectifier diodes -- replaced.

After that work was done, I put the preamp back in my office system, not thinking about it until Wilson Audio's announcement of the Reliable Capacitors acquisition. I had an idea, which I discussed with Daryl Wilson: replace the stock film capacitors in my Modulus 2D with Reliable capacitors and report on the sonic differences. Daryl was enthusiastic, and this project was born.

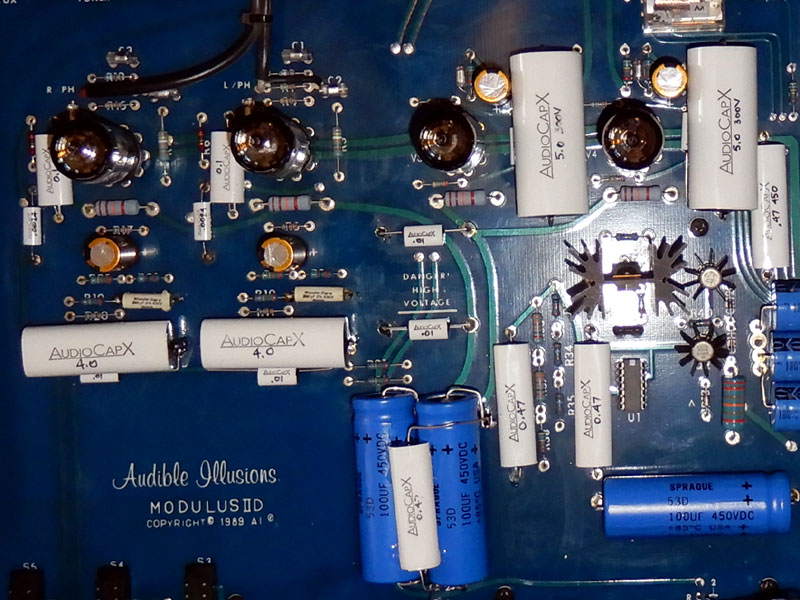

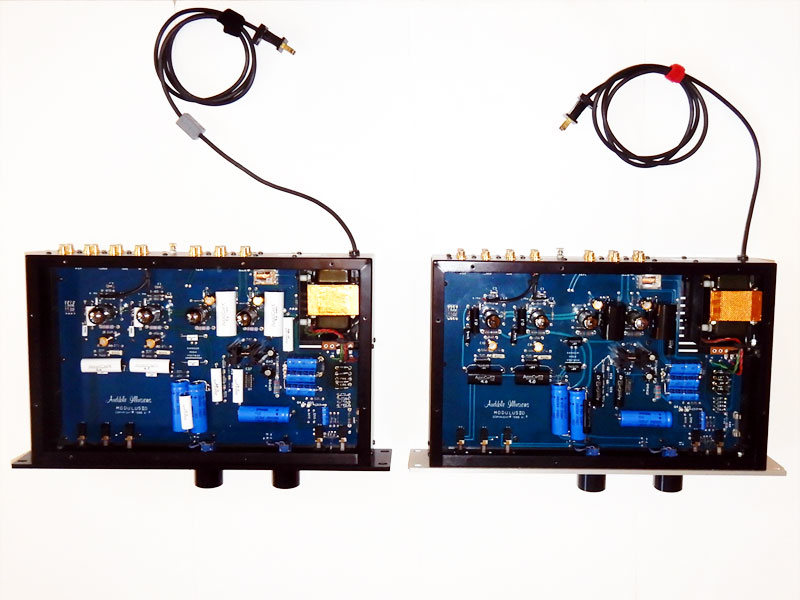

Modulus 2D serial number M2910604 before the film capacitors were replaced. I took an inventory of the Modulus 2D's film caps. There were 18 in total to replace, all Wonder Caps, in various sizes and values.

There was also a pair of 350pf, 630V, 1/2" x 1/4"D caps that were not replaced. Reliable doesn't make such a small value and they are used in the phono stage, likely for equalization. For this reason, Ken Stevens of Convergent Audio Technology, who is arguably the most zealous advocate of parts quality in the audio industry and consulted on this project, recommended they not be replaced. Because Reliable has multiple lines of capacitors, I discussed my needs with Blake Schmutz, the engineer at Wilson Audio who oversees the brand. He recommended Reliable's AudioCapX PPMFX multisection metalized polypropylene capacitors, because they were the closest to the Wonder Caps that Audible Illusions used in the manufacture of the Modulus 2. The day the Reliable capacitors arrived, I contacted the technician who would do the work, and the next day I took the partially refreshed preamp and new capacitors over to his shop. About a week later, the work was finished.

And then everything went a bit haywire, deepening the rabbit hole I had already crawled down, but in ways that ended up being helpful to this project and article. After I got the Modulus 2D with the Reliable caps back, there was a problem: hum in both channels. I took the preamp back to the technician who did all manner of testing but couldn't find the source of the hum. It wasn't the tubes and it was unlikely that it was the new caps, because, as the technician wrote to me, "No wrong values or bad solder were found." The only schematic for the Modulus 2D that I could find was hand drawn and of almost no help. The technician mentioned in passing that a second Modulus 2D would help him track down the issue, so I set about trying to find one. While many Modulus 2 preamps were made and thus come up for sale, the 2D seems to be a rare bird, perhaps because, as the final model in the line, there were fewer made, or their owners hold on to them. But I got lucky: a Modulus 2D that was exactly 500 units away from the one I had and looked identical internally (except for the new parts in my unit) came up for sale. I made an offer and got it, feeling good that the project would move ahead. Before the second unit arrived, there was a break in the case regarding the hum. The technician noticed a socketed IC on the circuit board that he hadn't tested. "I should have looked up what the IC was, the LM723. It is a voltage regulator IC that can operate floating. I just happened to have some NOS LM723s on hand and swapped one in, and the voltage came right down to +250VDC and no ripple and a quiet output." Translation: replacing the IC eliminated the hum.

But there was still the matter of the second Modulus 2D. When it arrived, serial number M2910104, I figured I would use it as a control for this project, but it also had a problem: distortion in one channel. This time, the technician was quickly able to discover the source: a single electrolytic capacitor, of unknown origin, in the right channel of the line stage. Because it was used for cathode bypass of the tube near it, it couldn't be replaced with whatever the technician had on hand, because it was sonically consequential. I began researching replacements -- for that cap and the other three in the same positions for the other tubes. I talked to Ken Stevens again, and he recommended Rubycon Black Gate caps. However, finding new Black Gates, which haven't been manufactured in decades, was nearly impossible. I needed four of them -- or eight, if I also decided to replace the same caps in the first Modulus 2D. More research, which ended when I found what I thought were the best replacements, both in terms of audio-grade electrolytic capacitors made today and those approximating the Black Gate caps of which Ken Stevens was so fond: Audio Note KAISEI. They were developed with Rubycon to be near copies of Black Gate caps, and according to text on the Parts Connexion website, the only difference between the two is that "the paper is not graphite impregnated in the KAISEI, otherwise they are essentially the same." The Audio Note caps were expensive for the value needed (470uF, 25V), about $10 each with shipping. I decided to swap out the caps in both preamps, reasoning that if one was bad, the other seven were getting there. The technician suggested doing the same with all of the large-value capacitors in the power supplies of both preamps, so he did that too, along with replacing the electrolytic capacitors and hot-running diodes, which was the first round of work done on the first Modulus 2D. I now had two preamps that were identical, except that one had the original Wonder Cap film capacitors and the other had Reliable AudioCapX equivalents. I did some comparative listening, which helped with this article, and then had an idea: replace the Wonder Caps in the second Modulus 2D with another Reliable capacitor. I posed this to Daryl Wilson and then Blake Schmutz, who suggested a mixture of Reliable's PPCuMFX copper metalized polypropylene and TFTCu Teflon/copper film and foil caps. Why the mix? Because Reliable doesn't make all values needed in each line and in sizes that would fit in the Modulus 2D. So another box arrived from Reliable, I took its contents to the technician, and he did yet another capacitor swap.

kay, so more than a year after this project was conceived, and several months after the first preamp was refreshed and then re-capped, I had a pair of identical Audible Illusions Modulus 2D preamps with different sets of film capacitors. I also swapped out all of the tubes, ensuring that the new ones, all NOS Amperex JAN 7308s, were as closely matched as possible. However, I still had one niggling issue to address: the dual volume controls. I needed to ensure that the balance between the channels for each preamp was identical and, just as important, that the output levels of the two preamps were identical. I did this with a pair of digital multimeters and a test CD. I set the output of each volume control at a predetermined level, marking it with a wedge of painter's tape. Now I knew that the output of each channel and both preamps was the same at those levels, and the painter's-tape wedges allowed me to eyeball settings with greater precision. I was finally ready to do more listening.

Right from the start, both of the recapped and refreshed Modulus 2Ds sounded better than a stock preamp: flatter in frequency, more dynamically alive, more defined, especially in the bass. They also sounded more like each other than they did the stock unit, but the differences were important. The second preamp, M2910104, with the mix of capacitors, sounded more liquid, poised and colorful -- more in keeping with a tube preamp than the first unit. The first unit, M2910604, with the AudioCapX caps throughout, sounded a bit leaner and more neutral in tone. Both sounded fast and open, though the first unit, perhaps because of its slightly greater neutrality, had a more obvious perception of speed. If I had to choose one preamp as sounding best, I would lean toward the second unit, with the mix of caps, but I often questioned this after listening to the other preamp for an extended period. A more important question, especially for this article, is: how significant are capacitors to the final sound that all products have? Of course, I can only answer that in the context of the Modulus 2D, because the design and execution of another product will be completely different. However, I can make some generalizations: that capacitors matter a great deal to the sonic signature of a product, so much that manufacturers like Reliable Capacitor exist. Audiophiles who own a Modulus 2D or another tube preamp will expend lots of effort and money finding tubes, often different kinds and vintages for both the line stage and phono stage, just to change the sound. I have done just this, and the difference can sometimes be profound. However, I would rate the capacitor swap as more sonically consequential. Its effects were fundamental to the preamp's overall character, not discrete or limited to one or a few areas of its performance. The best analogy I can give is an imperfect one from the fine-art world. In terms of sound, film capacitors are like an artist's canvas and paint -- the foundation on which the painting is created -- and the tubes are part of the color palette, which helps define the look and mood of the work.

Cost is always a consideration, and here it wasn't as great as I would have expected, given the sonic benefits. The full set of AudioCapX PPMFX multisection caps cost $127.62; for the PPCuMFX copper/polypropylene and TFTCu Teflon/copper set, the cost was $393.40. My local technician charged around $50 to swap just the film caps in each preamp, which put the final cost at less than $200 and $450 per preamp. Two matched pairs of NOS 6DJ8s can easily run $400 or more, and the sonic outcome, at least to my ears, is not the same as with either set of capacitors. Tubes also have to be replaced, whereas the film capacitors will probably last for as long as the preamp is in use. Another consideration specific to the Modulus 2: it is known to be hard on tubes. The preamp is completely off only when it's unplugged. It's in standby when plugged in, even if its power pushbutton is in the off position. In standby, the heater supplies for the tubes are on -- you can see the tubes glowing through the ventilation holes in the top cover. Therefore, return on investment for tubes has a shorter duration by default. So what did I learn from this exercise, which took over

two years from conception to completion? Passive parts are foundational to the sonic

signature of any audio product, and film capacitors matter more than even vacuum tubes.

Reliable sells directly to consumers, so if you have an older piece of gear, are good with

a soldering iron (I am not), and want an audio project that will make an easy-to-hear

sonic difference, get the Reliable Capacitors price list and mix and match to your ears'

content. |